A broad range of research by art historians on the positive but complex practice of feminism during the Moghul period had lead to rich comprehensively examined information. The complex socio-political, historical, and religious factors cultivate into an iconic framework in which the contributions of Princess Jahanara Begum stands up to the tallest. Her enriched approach in her choices of patronage, piety, poetry, and political diplomacy within the pressures of male-centered methodology received serious attention to detail and reverence among Moghul Emperors and Imperial males. Casting Princess Jahanara’s life and contributions in the historical framework not only endorses and locates her a place in the Moghul hierarchy but above all in history both in text and form. She was an elite Muslim woman, seems to occupy a separate and much higher level, not in the same realm to the Muslim male counterparts. For most of the Mughal females who were “bold, unbecoming, and masculine” are only marginal ‘fillers’ of spaces in historical biographies of Mughal men. Even the counterproductive to sustaining sovereignty as in the case of Nur Jahan has been widely discussed. Nur Jahan’s political machines, her mode of power, her representation to the Empress’s profile, patronage of art and architecture and historicism of her works alongside Mughal males were discussed widely. However, she didn’t authored text or even personal accounts. She was a contested Queen against her male counterparts. Her assumptions of power are not to be her successes. It was due to the failure of her husband, Emperor Jahangir, to control many of his mistresses. Rare but not absent is a Mughal woman’s voice that is enunciated through her writings. The one eyewitness account of the early Moghul life were accounts and narratives of Gulbadan Begum in her unfinished memoir on her brother Humayun’s reign. However, she began with her father Babur’s kingship and the details of life. Gulbadan faithfully recorded and cultivated a unique & vibrant perspective of early Timurid- Mughal life of both men and women. Gulbadan as an author, historian, and documentarian, are clear precedents for Jahanara Begum’s writing of her two Sufi treaties: “Risala- i- Sahibiyah” (1640) and “Munis- al- Arvah (1638)”.

However, unlike the Humayunama, the treatises were used to explore the multiple ways that Jahanara Begum established new precedents for female piety, patronage, and political diplomacy. It questions and modifies not only to the existing modalities of practice and representation for royal females but offers through her treatises a more textured, nuanced, and vocal understanding of female history. Further research on Jahanara Begum’s life and contributions critically examine her persona as a function of her writings, patronage, and piety. It discusses how the princess accepted and negotiated with the prescribed Imperial and religious values and, more importantly, how these were modified and recast into the Moghul landscape. It is broadly thought-provoking in Moghul women’s contribution as commissioned Urban landscape builders. Jahanara Begum notably showed major emboldened high profile commissions in ordering other women builders when Shahjahanabad was constructed. Jahanara Begum did not function in a vacuum without influences or resistance. A prevailing interest informed the poetry she wrote of the Moghul court. For the Moghul warrior- aesthete, poetry to them provided decency to the treachery and savagery experienced both in the courts and the battlefields. For them, the patronage and promotion of poetry dulled the harsh realities and allowed the nobles to bathe in the ether of sublimity.

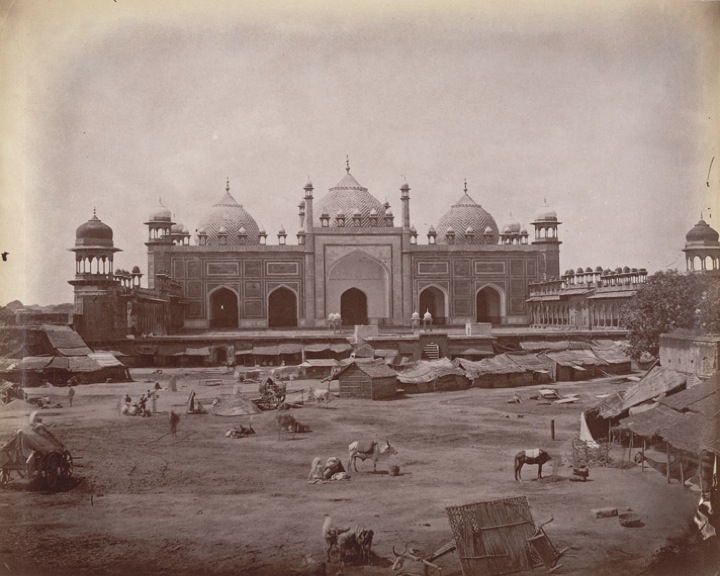

The institution of seclusion and Imperial etiquette have been a mark of the Islamic world through the ages. As a result, women of the social order, women of the Moghul dynasty in India, led sequestered lives where their character was largely hidden from public consumption. Imperial women publicly conveyed spiritual and political well-being through the giving of alms or commissioning major sacred-secular monuments. The Agra mosque built by Jahanara Begum is analyzed as an example of the princess’s ‘official’ persona. Whereas the Mullah Shah Mosque and Khanaqah complex can be considered her private and more personal representation.

The personal and passionate narratives contained in Jahanara Begum’s Sufi treaties are modes of empowerment that facilitated the unmarried princess broader social, political, and religious participation. Her authentic, active, and visible engagement extended to the political realm where she stood tall uncontested, revered with political authority along Imperial male hierarchies.

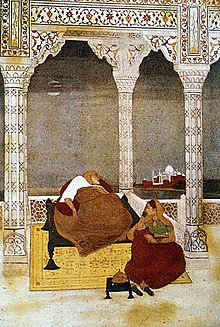

At the tender age of seventeen, Jahanara became the First lady of the Mughal Empire. The untimely demise of Mumtaz Mahal allocated half of her property worth ten million at that time to the Princess. The royal seal was entrusted to her. Over time, Jahanara became the wealthiest woman in the world at that time. She owned several beautiful gardens. Her ships were docked in Surat that took a voyage of Europe for the trade. The European royalty wore Indian silks and muslin in their grandeur. Her designs were favourite that attracted the European to trade markets with India. Although the wealthiest lady, she had a very kind heart. She accepted self-imprisonment along with her revered father, Shah Jahan when he was imprisoned by Aurangzeb. The ailing Emperor suffered from a venereal disease in prison, it was his daughter Jahanara that lay beside him on the floor as long as he was alive. In a voluntary house arrest, she devoted all her time to her father, cautiously watching him after his safety till his death.

With brother & new monarch Aurangzeb, the Sufi princess maintained a cordial relationship. He knew that she never supported his treachery. But he revered Jahanara the most, & had absolute faith in her than any other. She openly sided Dara Shukoh with money, soldiers and weaponry. Jahanara tried to convince Aurangzeb not to put up with the fight, to follow the path of loyalty but to no avail. Her greatest gift was to Delhi, the Chandni Chowk “Moonlight Square.” In the path of Sufism, she was disciple of Mullah Shah Badakshi, a Sufi of Qadri order, who became spiritual mentor of both Prince Dara Shukoh & Princess Jahanara. The princess left the world for heavenly abode in 1681 & was buried near the shrine of Chishti Sufi, Hazrat Nizamuddin. The burial site was chosen by the princess & open to sky white marble tomb was build by her during her lifetime. The resting place of 17th century richest lady is reflection of a simplicity acquired by her Sufi affiliations.

Almighty God is the Living, the Sustaining.

Let no one cover my grave except with greenery,

For this very grass suffices as a tomb cover for the poor.

The mortal simplistic Princess Jahanara,

Disciple of the Khwaja Moin-ud-Din Chishti,

Daughter of Shah Jahan the Conqueror

May God illuminate her proof.

Pic source: Wikiimages

Dewali Deb is a writer from India. She writes almost every genre & has been engaged in teaching high school board students for more than three decades.

A Master's in English Literature along with few other degrees and certificates.

This is a complete tribute to the Princess, in words and colourful illustrations. She possessed a larger than life image. An Universal conspiracy conspired to her credit, bestowed upon her blindly with Grace and wisdom.

Princess Jahanara Begum, being a decisive historic feminist legend, deserves more steady mention for the present and upcoming generation.

Thank you to all.

Thanks Dewali for this wonderful write up